When I was nineteen, a kid asked me what a feminist was.

“A feminist is a woman with an authority problem,” I said.

It was a black-and-white world I lived in then, one where I had all the answers (because I had read them in a book) and I wasn’t afraid to tell them (because I was nineteen).

I was the least likely person to ever become a feminist.

///

The world I grew up in was pure, concentrated patriarchy.

Wives and daughters were subjected to the “headship” of men – no decision was to be made without the permission of the husband or father. Family planning, pants, college, and outside employment were all frowned upon; a woman’s place was at the kitchen table, homeschooling a gaggle of obedient children.

When I was sixteen, I told a friend that I didn’t see any reason for girls to go to college. After all, what’s the point of going to college if you’re going to stay home raising kids for the rest of your life?

I thought I was going to be a pastor when I grew up, and I was hoping to someday find the ideal pastor’s wife: A girl whose main ambition would be raising our children and supporting me as I “pursued my calling.” I would make the arrangements for the relationship with her father; she would wait patiently while I got his permission to woo her.

///

By the time I was in college, I had moved out of the ultra-patriarchal corners of the conservative homeschooling movement and joined the broader streams of popular conservative Evangelicalism. Though not as extreme, some of the same assumptions were present here: A man was to provide and lead, and a woman’s place was in the home.

When I was at work I’d listen to sermons on my iPod about what it meant to be a “real man.” The masculinity I heard preached was exciting – glorious, honorable, rough, violent. It eschewed “limp-wristed girly-men” and stay-at-home dads alike. A man’s job was to work hard to provide for his family; a woman’s job was to take care of the household and children and always be cheerfully available for sex.

It was a vision of masculinity perfectly designed for my black-and-white view of the world.

///

Sarah and I were dating by then and we read Christian marriage books that continued to reinforce these binary gender stereotypes. Men need respect, women need love. Men give love to get sex, women give sex to get love. Men want to fight for a woman, women want to be rescued. Men defend and provide, women comfort and nurture.

But shortly after we were married, we began to realize that we did not fit into the neat boxes so often prescribed by preachers and books. Not only were our expressions of our gender roles not so narrow and fixed as I had once imagined, but perhaps “Biblical manhood” and “Biblical womanhood” were not so reductive and monolithic as I had believed them to be either.

///

Through most of these years, I was a pretty dogged conservative – I had a McCain sticker on my bumper and listened to Rush Limbaugh every day on my way to work.

I heard the same messages about feminism from the radio that I had heard from the pulpit growing up: Feminists hated men and children. Feminists were rebellious and dangerous. Feminists were responsible for the decline of masculinity. Feminists, along with liberals and gays and immigrants and Muslims and atheists, were going to usher in the fall of America.

I was oblivious to my privilege as a straight white male. I had grown up near or below the poverty line… what possible privilege could I have that others didn’t? Like the voices I heard on the radio, I believed that that everyone was the master of his own fate. After all, wasn’t the beauty of America that it’s a land of opportunity, a level playing field?

I was unable and unwilling to see my own sexism, my own racism, my own homophobia: my own privilege.

///

Though I would have resented the suggestion, I was simply narrow-minded – convinced that what I was believed was right, though I had never honestly examined it. It was a benevolent arrogance – the sort that comes from memorizing the right answers without ever truly questioning your own worldview.

During college I had a sort of crisis of faith (which I’ve touched on here and will some day write about at length) and in the aftermath of that I found myself exploring questions I’d never really allowed myself to ask before. I didn’t find answers so much as I realized how few answers I actually had.

And in the absence of answers, I found empathy.

Slowly, I began to realize how self-centered my world was – not that I didn’t care about others, but I had rarely truly considered the world through any lens but my own. Clumsily, I attempted to replace hate with understanding.

///

By this time I’d already read the Bible through at least half a dozen times; after a while it starts to all blur together. Characters were reduced to bullet points; heart-wreching accounts were skimmed quickly and then checked off a list.

I was shocked, then, to read those stories as if for the first time and think about what the women in the Old Testament endured. The kidnappings, rapes, and murders littered so plentifully throughout the Scriptures.

And for the first time, I realized that perhaps we were supposed to feel some compassion for them – these women caught in a tragically cruel system that all too often treated them like property and political pawns.

For so long I had hit the bullet points, interpreted the theology, parsed the context, but failed to even consider the humanity of the women whose lives and deaths were recorded on those pages.

///

It was around that time that I stumbled upon my first “Jesus Feminists.”

First there was Rachel. Then Sarah, Emily, Suzannah, Preston, Hännah .

I was confused, at first. They didn’t seem like haters of God and men, or destroyers of families and America. But there was that word – “feminist.” That label I had been taught to fear.

They loved the Bible. They loved their husbands and kids. They loved Jesus.

But they called themselves “feminists.”

As I listened to these voices from outside of my relatively narrow context, as I read the Bible with a fresh perspective, I saw how many false assumptions I had accepted.

I realized that the “Gospel-centered manhood” promoted by so many leaders didn’t always have much to do with the Gospel. I realized that the violent masculinity that I’d admired wasn’t consistent with the Jesus who showed us that God can bleed.

///

“You should become a feminist,” I’d say to my wife, half-jokingly.

It was a strange word on her tongue too, but I think the language of feminism gave her words to express things she’d always experienced but never quite been able to say.

About how she’d been silenced. About how she’d been made to believe that God spoke to men but not to her. About how she’d believed that her passions and dreams had to be buried for the common good.

For both of us, I think, there was freedom in these conversations. In not assuming “traditional” gender roles imposed on us by preachers I’d stopped listening to years ago. In exploring the reality outside of generalizations that had never fit us quite right.

What if she wanted to go to work, and I wanted to stay home? What if she was strong and wise and I was caring and compassionate? What if she went to the gym every morning and lifted weights while I bathed the kids and fed them breakfast and washed dishes?

///

I stopped listening to the men in suits and their the fear-mongering doomsday predictions about feminism. Instead, I started listening to feminists talk about what feminism meant to them.

What I heard wasn’t hatred or bitterness or anger or arrogance. I heard brave, strong voices. I heard hearts turned toward love and justice:

“I define feminism as the simple belief that women are people, too. At the core, feminism simply means that we champion the dignity, rights, responsibilities, and glories of women as equal in importance to those of men, and we refuse discrimination against women. That’s it.” – Sarah Bessey

///

There are a few phrases of Scripture that ring in my ears when we talk about feminism – words about doing justly, about loving mercy. Words about letting justice and righteousness roll down like rivers. And most of all, those words about how every valley will be exalted and every mountain and hill made low.

For a long time, men have enjoyed a mountain of privilege while women have been relegated to the valleys.

But in the Kingdom of God, those who are elevated must surrender their privilege and lift up those who are low. This is why equality matters to me. This is what I invite when I pray, “Thy Kingdom Come on Earth as it is in Heaven.”

At the heart of my faith practice is Jesus’ teaching that I am to love my neighbor as myself. How can I love another as myself if I hold tightly to privileges they cannot enjoy? Doesn’t love seek the good of others? Doesn’t love lay down its life for its friends?

And so, it wasn’t a women’s studies class or intersectional theory that made me a feminist, but those simple, familiar words from the ancient holy Text:

“You shall love your neighbor as yourself.”

///

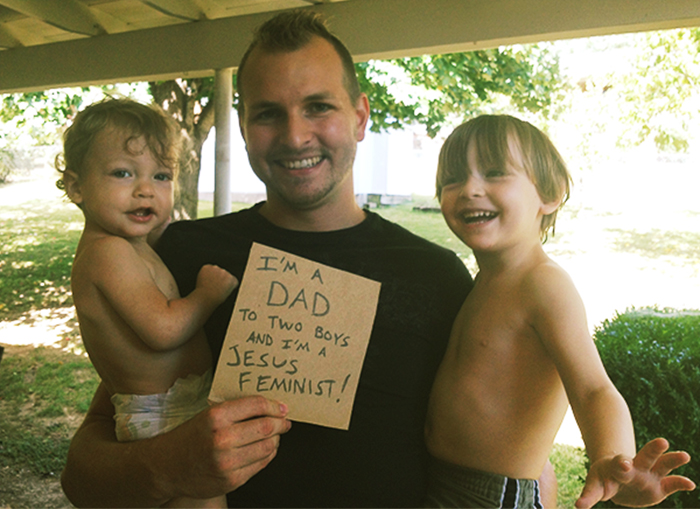

I kept trying on the label, casually for a while. And then it stuck.

If feminism is about justice and equality for women, then call me a feminist.

But the label isn’t what matters to me. What matters is learning to surrender my privilege and listen to the strong, brave voices of my sisters.

About a week ago, I wrote a thing on the internet challenging the notion that men are being emasculated by feminism. I wanted to turn a mirror toward us to help us realize all the ways in which we still benefit from a system tilted in our favor.

In the past week I’ve seen even more just how much we need feminism. I’ve heard stories over and over from women whose voices and gifts have been silenced simply because of their gender. And sadly, I’ve heard a lot of angry words from men determined not to yield the mountaintop.

I’m still very much in the middle of this mess. I still have more questions than answers – about how to understand the Scriptures, about family and church leadership, about gender and masculinity and femininity, about how to raise my boys to be strong loving men.

So call me a feminist if you want, but please don’t call me an expert. I’m still learning. I still have a long way to go.

I wrote a thing that a lot of people read, but now I mostly want to sit back and listen.

Because women are speaking up, and it’s time that their voices were heard.

published November 20, 2013

subscribe to updates:

(it's pretty much the only way to stay in touch with me these days)